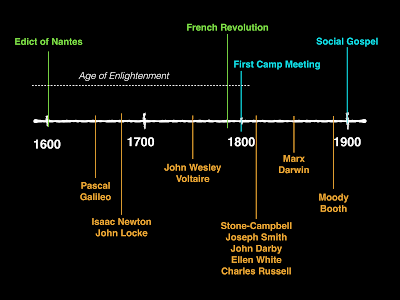

NB: For readers who missed it, I suggest going back to review my setup to this section on church history to know about my disclaimers. For the graphics used in this post, the timelines are not to scale, and the dates represented are not intended to be exact. They are meant to be visual aids for understanding the larger conversation.

Fundamentalism and secular humanism continued to be locked in a fierce battle for “truth” for a decade. It would be worth answering the question that often goes unanswered in these conversations: What happened to the parts of Christendom that wouldn’t have aligned with fundamentalism? At this point in history, those who would have rejected fundamentalism often drifted towards theological liberalism. While the Church (in this century) would eventually learn how to have more progressive conversations and put more “options” on the table (rather than a simple bifurcated presentation of the argument), this is not that point in history. For much of [theological] liberalism, their position felt like a weak take on humanism, with Jesus slapped on the label.

The two options most 20th-century Christians had to choose from seem today like equally bad options; it also looked like Christianity, while putting up a good fight, was not going to have the staying power to outlast the run that humanism was putting together.

But that all ended with the arrival of World War II.

Any hope that humanity could usher in some utopian societal existence, whether it was by fascist, socialist, communist, or even democratic means, would come to a crashing end. Every humanistic worldview seemed to show its true self in the face of unbelievable genocide, communist oppression, and nuclear war. Simply put, humanity isn’t as great as we thought it was.

This gave Christianity a great and sudden turnaround that ushered in what I call the modern evangelistic era, and the eventual rise of the evangelical church. Fundamentalism gives way to a broader, softer version of itself in a wide representation of Protestant, American Christianity. While the beliefs that justify “evangelical orthodoxy” change depending on who you ask (even today), modern evangelicalism attempted to plant its flag and set up its defenses. It’s worth noting that we still find ourselves in this tension today. The “culture wars” of the current evangelical church are not the great Promised Land of our day, nor are they the last and final Armageddon we often want them to be. At best, they are simply the awkward phases of a modern evangelicalism that is going through a sociological “puberty” and, at worst, they are the final gasping breaths of a movement coming to a very unflattering end. We would do well to consider these things.

The modern evangelical movement was created by some of the greatest evangelists of our era. People like Billy Graham and Bill Bright (founder of Campus Crusade for Christ) helped the church navigate this very difficult era, giving the Church language for communicating the gospel like we had never seen. I believe history might look back on this era with a similar perspective to our view of the printing press and the Reformation. This modern evangelical push paved the way for cultural engagement like never before.

Evangelism was now in the hands of normal, everyday parishioners — not just the clergy and preachers in revival tents. The creation of the “Four Spiritual Laws” (no matter how you or I might feel about their theological accuracy) created a world where college students, coworkers, and soccer moms could articulate the movement of Jesus in simple language. The same resurgence of cultural engagement would eventually lead to what many from the 1970s call the “Jesus Movement” and the great testimonies of the movement of Jesus in people’s hearts.

About the same time (the 1970s), the world of biblical scholarship was experiencing a new frontier, as well. While this is highly oversimplified, the work of Jacob Neusner changed the world of hermeneutics as we know it. Neusner, a Jewish literary scholar (not a Christian), was attempting to understand how modern Christian thought had influenced Jewish thought. As he brought modern Christian scholars (mostly Catholic) to the table, they found themselves learning lessons from Judaism that had gone missing some 1800 years ago. Realizing the impact this had on our understanding of the Bible, academic Christians would never again engage in scholastic research or archaeology without the aid of their Jewish brothers.

Many people have asked me, “How could we have not known this stuff for all these years?” The ridiculously simplistic answer is that we just hadn’t asked. Until the work of Neusner and others, Christendom had been too worried about doctrinal purity and theological rightness to ask basic questions about the Bible’s long-lost Jewish context. Since the turn of the century, many evangelical churches are beginning to experience the work of these scholars, finally “turning the corner” to our common knowledge.

I had professors who told me in college that new discoveries often took 20–30 years to find a presence in the Church. These new discoveries have to be vetted and then handed to the educational institutions (universities and seminaries), and then taught to the eventual pastors who would teach these things from pulpits (and through blog posts). Now, with the rise of the Internet, the distribution of this information — and all information (good and bad) — is increasing exponentially.

But that’s not the only thing that changed at the turn of the century. The world of science had also taken an unexpected turn. While the modern era produced a scientific belief that we would be able to figure out everything if given enough time (see how this fits so well with secular humanism?), the discovery of quantum science radically changed all of that. Some of the most basic principles of physics and Newtonian movement no longer applied in quantum science. The scientific world reeled in the implications of this development.

Combine this with the sociological realizations of this century, and we have a major shift in worldview. While humanism took a major hit, secularism was (and is) far from dead. In fact, since the days of the French Revolution, this might be the most shocking shift Christendom has yet to accept. While we talk about it often (“post-Christian culture”), we have not figured out how to respond well to it.

Enter: Postmodernity.

In the late 1990s, the cultural cry became, “What do we truly know, anyway?” Whether it was society or politics or science, it seemed like absolutes weren’t as absolute as we had once thought. While the Church cried out against what they perceived as moral relativism, the world moved on anyway. Some progressive evangelicals attempted to move with this cultural change, bringing the gospel back into the cultural conversation by creating what is known as the Emerging Church. Largely rejected by Evangelicalism (and, I would argue, no longer considered a viable approach to the “new day” of Christian thought — at least in its original form), the Emerging Church helped start some conversations that would set the stage for growth the Church needed to prepare for its survival.

And now, a decade or two later, we find ourselves at today. With the rise of decentralized consumerism (Uber, Airbnb, etc) and social networks changing the language of interaction everywhere, it’s hard to know exactly what lies just around the bend. Where is God calling us and what does any of this mean? Is there any hope at all for the future of Christianity? It seems like we have devolved into such a mess that it's hard to know what God would even approve of in our efforts.

Well, in fact, I believe we find ourselves (as every generation has) perfectly placed for the future.