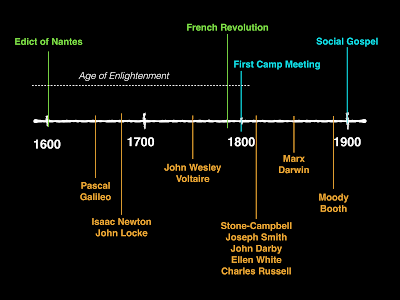

NB: For readers who missed it, I suggest going back to review my setup to this section on church history to know about my disclaimers. For the graphics used in this post, the timelines are not to scale, and the dates represented are not intended to be exact. They are meant to be visual aids for understanding the larger conversation.

As the age of revolution changed the cultural setting for Christendom, there was a new push to get our bearings as a faith movement. For almost 1400 years, the world of Christendom had enjoyed being the privileged default of culture. If you unplugged the western world and plugged it back in, the default setting would have blinked “Christian.” But now, with the rise of the Age of Enlightenment, Christendom’s white-knuckle grip on theology, creeds, and doctrinal truths did not age well. As the world became more and more knowledgable, more and more educated, more and more literate — simply affirming creedal beliefs wasn’t holding a candle to the scientific method.

But before we talk about science, one has to talk about the this new culture of independence and the impact it had on our own shores in America. The movement of culture away from Christianity had a positive effect for Christendom as a whole. In an effort to regain what was being lost, Protestant believers fell into what is often referred to as the Second Great Awakening (the “First” Great Awakening is usually attributed to the rise of Methodism in the mid-1700s, which we discussed previously). This great time of ‘revival’ was ushered in throughout North America and Europe through what we commonly know as “camp meetings.”

These revivals became a time for denominations to come together and enjoy fellowship, worship, and preaching. Such a focus and desire to experience true confession and repentance would lead to great times of spiritual revival and movement. Many attribute the rise of Pentecostalism to these experiences where the Holy Spirit seemed to be poured out in abundance. What is widely accepted as the first camp meeting was held in Kentucky in 1801 and would set the stage for an invigorated and passionate movement of Protestant parishioners.

This same awakening, coupled with the cultural movement of America toward freedom and independence, led to the jettisoning of denominationalism. As many denominations were attempting to hold onto their imperial moorings through the use of creeds and belief statements (think of a more colonial version of ‘church membership’), entire groups began kicking against colonialism as it was experienced in the North American church. The Stone-Campbell movement (also known as the Restoration Movement) was started when Barton Stone, a recently ordained minister of the Presbyterian Church, was asked to sign the Westminster Confession before he could receive the Eucharist. Appalled by the use of Confession and doctrine in this way, Stone joined others with similar encounters to restore a sense of the faith experienced in revivals (a faith they associated with the early church in the book of Acts) to Christianity in America.

It is not a coincidence that other movements started at this time, as well. Driven by the same disgust in the direction of Christianity, Joseph Smith received his calling (Mormonism) at this point in history, and we see the work of Ellen G. White, John Darby, and Charles Russell (Jehovah’s Witnesses). Note that all of these movements are capitalizing, albeit unintentionally, on a newfound culture of freedom and independence to start new, revived expressions of a faith they felt was corrupted and dying.

On the scientific front, things are not turning out well for any form of Christendom trying to hold on to the doctrinal confessions and creedal understandings of their faith. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Charles Darwin began his famous work and Karl Marx was pursuing new political ideals; both seemed to work against a Christian worldview. While many of these ideas were critiqued within the Christian worldview, some critical thinkers in Christianity were affirming certain components.

The need for social vigilance was championed by people like William Booth, the Methodist pastor who founded the Salvation Army. Booth would become one of the lead thinkers shaping Christianity’s social consciousness around the turn of the century, giving rise to what we would call the social gospel. While the term has a negative connotation in most conservative evangelical circles, the movement was simply trying to recapture the practical and misplaced emphasis on caring for the poor and marginalized in our increasingly industrialized world where the gap between the rich and the poor was rapidly increasing. These were some of the same things that modernity — in all of its socio-polical growth pains — was trying to articulate, as well.

The secular aspect of this cultural growth curve is known as secular humanism, and after we finished fighting World War I (it’s interesting how war always hinders progress), Christendom in North America turned its attention to fighting these secular ideals. Like a lit powder keg, the famous Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee, led to eruption of Christian “fundamentalism.” Christians immediately saw themselves in a culture war with secular humanism. The problem is that this rings incredibly reminiscent of the mistakes we made with Copernicus and Galileo. It seems we may be in danger of misidentifying our “enemy” and the truth we should be fighting to preserve.

But with all the splintering and division of Christianity, it becomes harder and harder for us to learn from our mistakes.